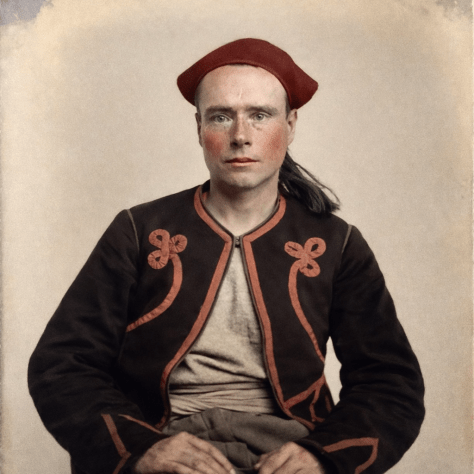

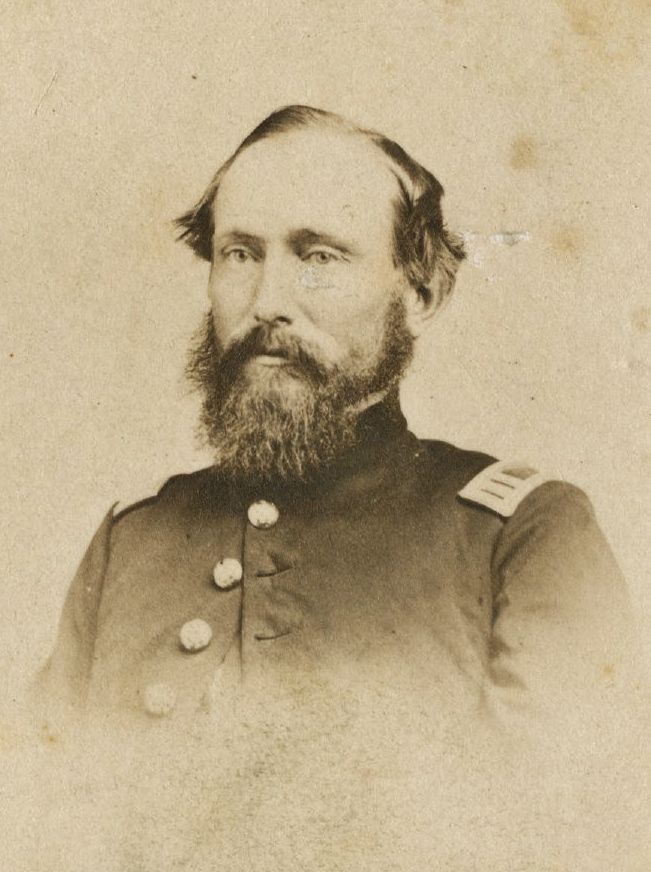

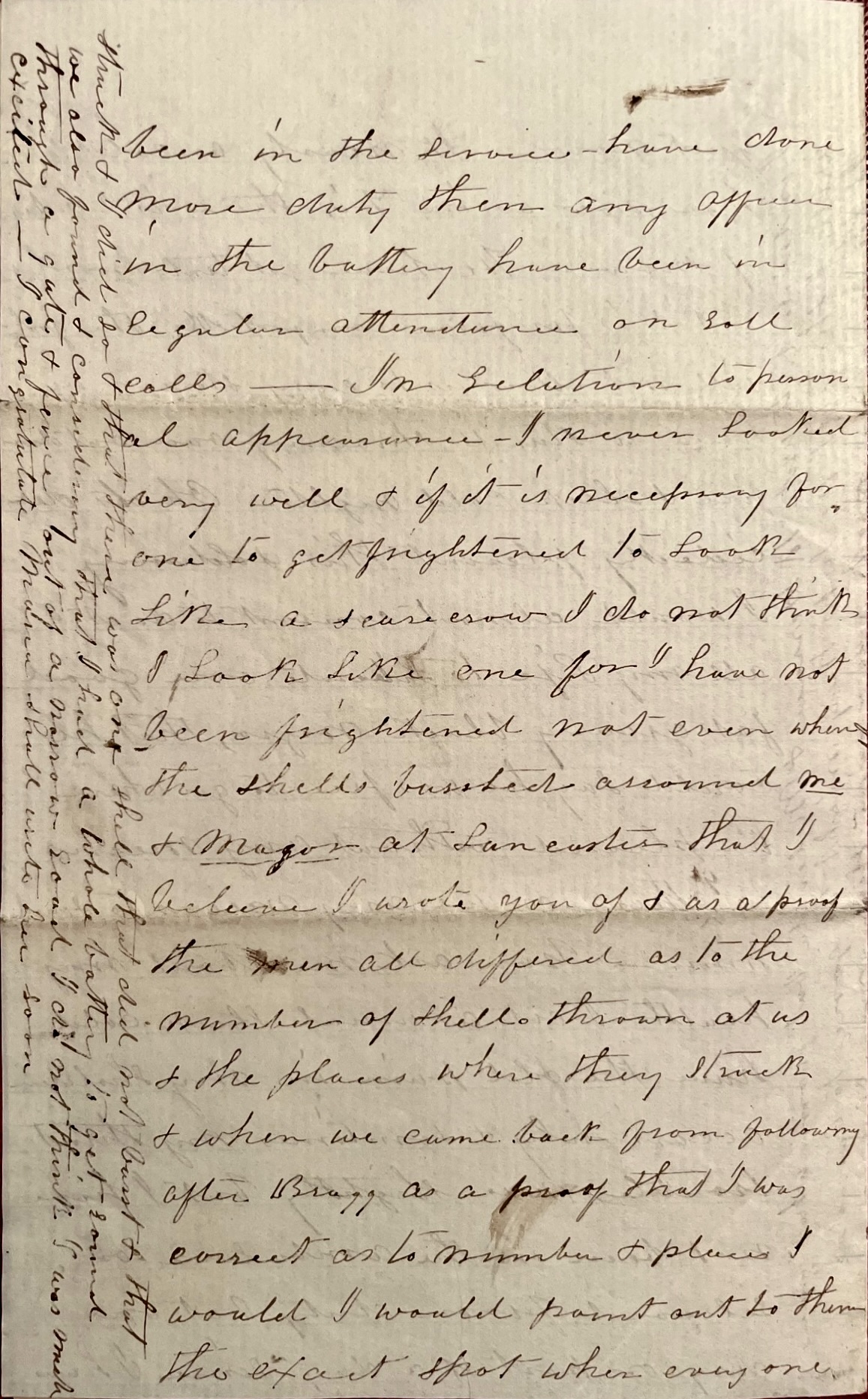

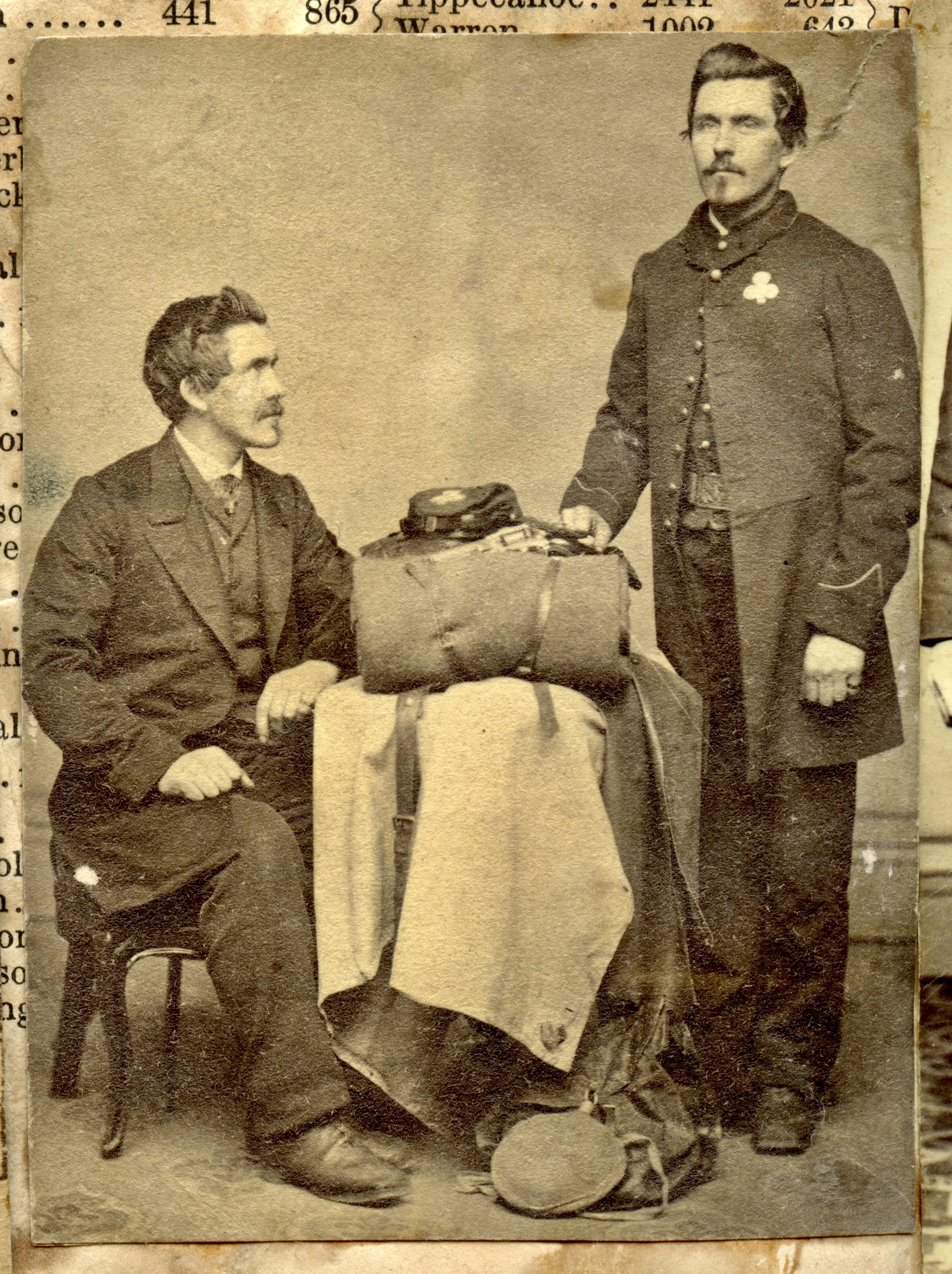

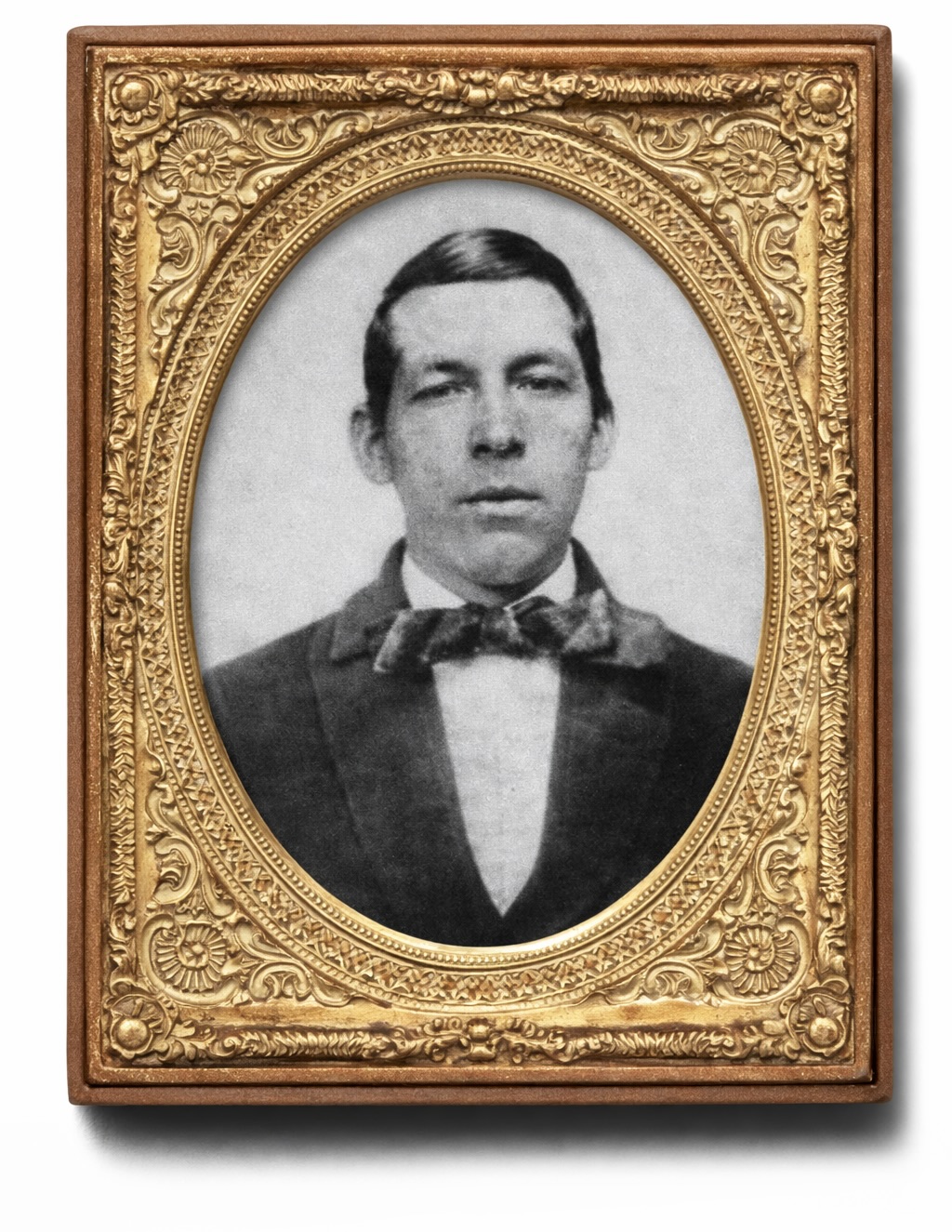

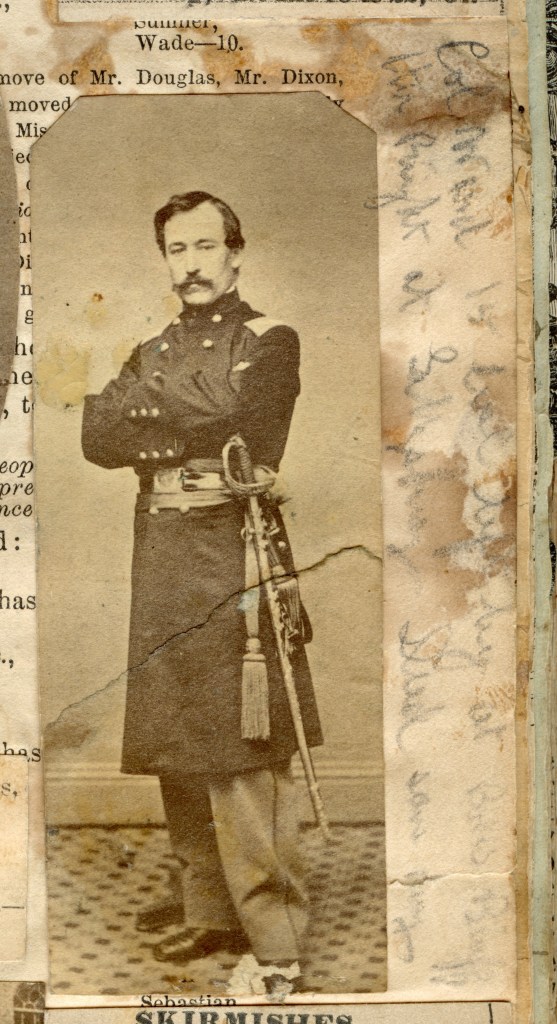

The following memorandum of the Battle of Gettysburg was written by Amos Chatman Plaisted (1844-1902) of Co. B, 15th Massachusetts Infantry. Amos was born in Dec 1844 at Haverhill, Grafton County, New Hampshire, son of Elisha Plaisted (1805-1873) and Hannah B. Huntley (1821-1847). At the time of his enlistment in July 1861, Amos gave his occupation as “machinist.” On his way to war, Amos wrote his parents, “We had a first rate time all the way from Worcester. We came through Connecticut, New Jersey, Pennsylvania, Delaware and Maryland — so I have seen many of the largest cities in the union, and now I want to fight and have the war settled! then I shall be contented to settle down in the shop again. But don’t worry about me, for all I want is strength to do my duty, and if I fall — so be it!”

It is my opinion that this memorandum was written some years after the war and for the benefit of his son, Edgell R. Plaisted (b. 1870). My guess would be that it was written about 1890. It was found in a scrapbook kept by Amos and acquired recently by Paul Russinoff who made it available for transcription and publication on Spared & Shared by express consent.

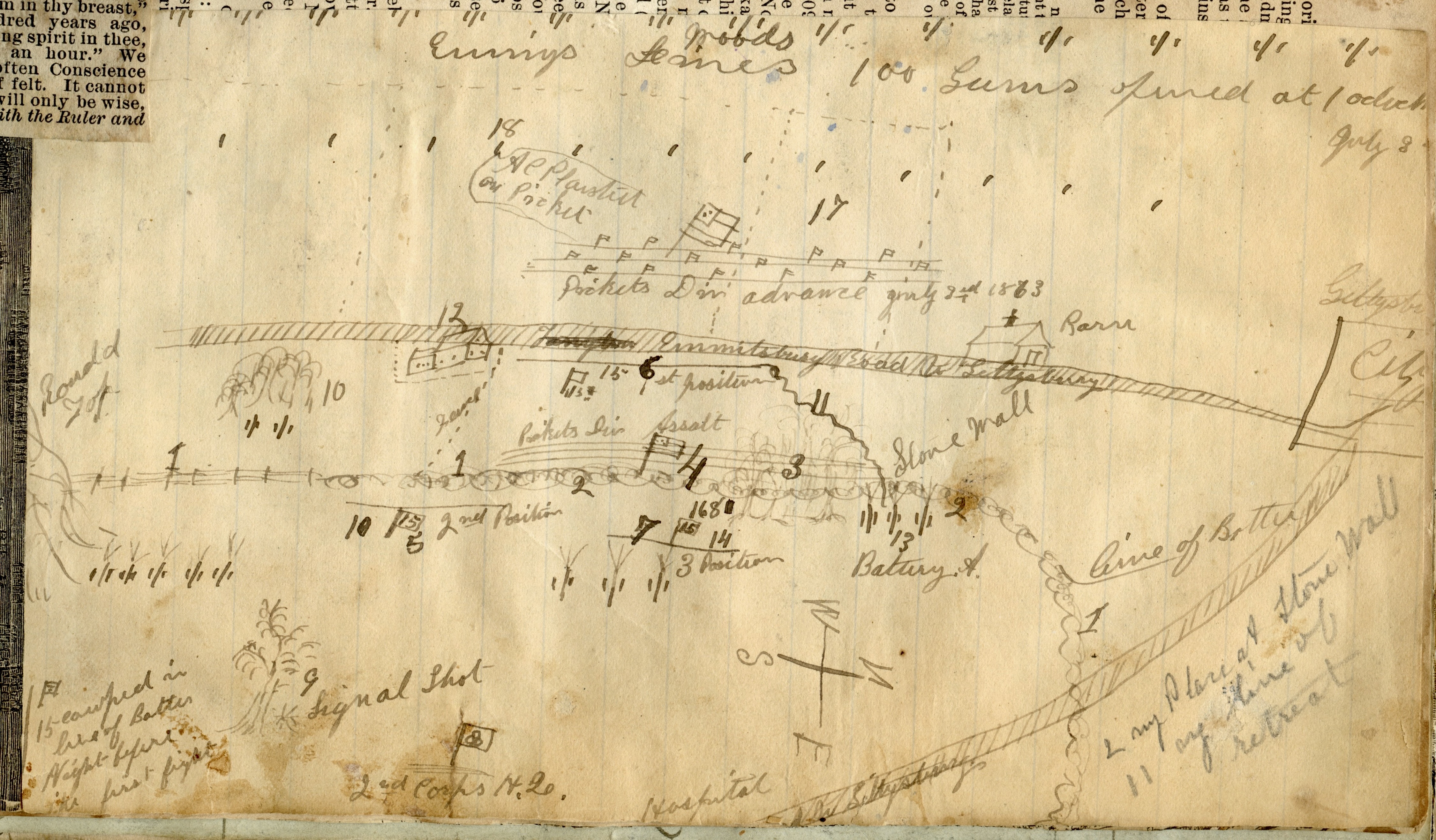

In the mid-1880s, the 15th Massachusetts infantry placed their monument on the battlefield at Gettysburg just south of the copse of trees where its members were fighting at the time that “Picket’s Charge” was ultimately repulsed. It was later determined by the Gettysburg Battlefield Memorial Association that regimental monuments should be placed on the battlefield where the regiments first lined up in battle formation, not where they ended up, so the 15th Massachusetts monument was relocated to a point some 200 yards further south on the Federal line. This ruling did not sit well with some of the veterans of these regiments who helped turn back the Confederate assault near the copse of trees and wished to see their monuments remain at the center of the action. Memoirs such as this by Plaisted may have been written in part to make certain historians did not forget their contribution in winning the day.

T R A N S C R I P T I O N

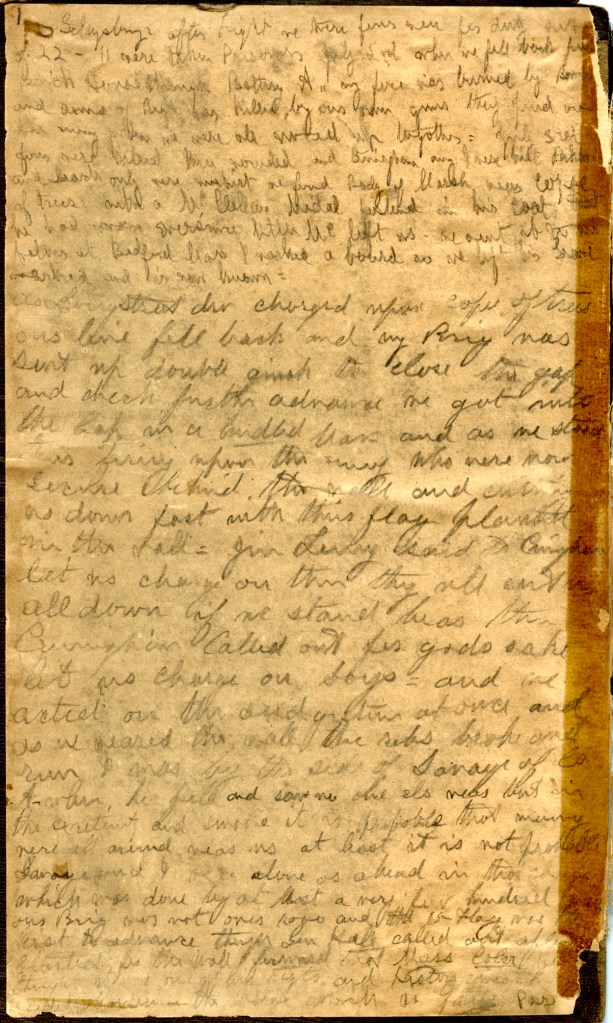

Gettysburg. After the fight we were four men for duty out of 22. Eleven were taken prisoner July 2nd when we fell back from the Brick [Codori] House through Battery A. My face was burned by powder and some of the regiment was killed by our own guns. They fired on many when we were all mixed up together.

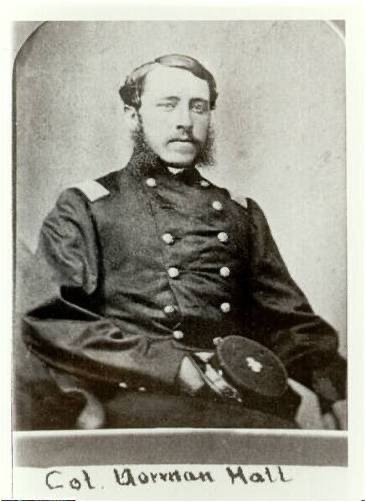

July 3rd, four were killed, three wounded and [George] Cunningham and I were with Peckham and [Flavel] Leach only were unhurt. We found the body of [John] Marsh near copse of trees with a McClellan medal fastened on his coat that had worn ever since Little Mac left us. We sent it to his father at Bedford, Mass. I marked a board so we left his grave marked and is now known.

As Longstreet’s Division charged upon copse of trees, our line fell back and my Brigade was sent up double quick to close the gap and check further advance. We got into the gap in a huddled mass and as we stood there firing upon the enemy who were now secure behind the wall and cutting us down fast with their flag planted on the wall, Jim Tenny [of Co. B] said to Cunningham, let us charge on them; they cut us all down if we stand here. Then Cunningham called out, “For God’s sake, let us charge on boys!” and we acted on the suggestion at once and as we neared the wall, the rebs broke and run. I was by the side of [Sgt. William Henry] Savage of Co. A when he fell and saw no one else near but in the excitement and smoke it is probable that many were all around near us—at least it is not probable Savage and I were alone or ahead in the charge which was done by at least a very few hundred men.

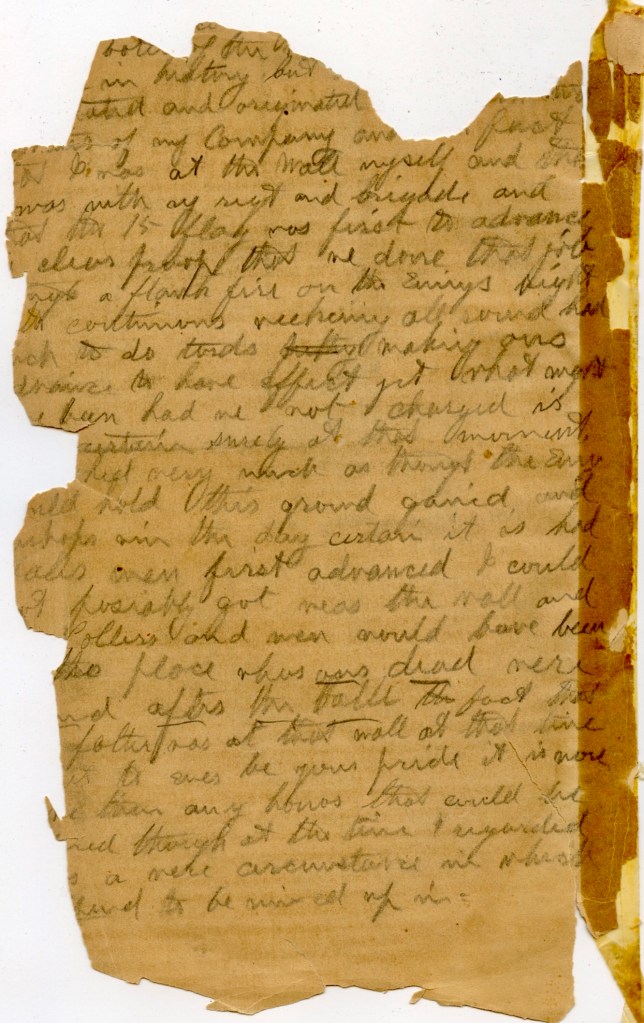

Our Brigade was not over 1,000 and the 15th [Massachusetts] flag was the first to advance though Gen. [Norman J.] Hall called out as we started for the wall, “Forward, that there color!” I thought it was one of his regiments and history gives to credit [writing illegible] which is false …of my company and in fact [ ] that I was at the wall myself and that [ ] was with my regiment and brigade and that the 15th [Mass.] flag was first to advance is clear proof that we done that job through a flank fire on the enemy’s right. The continuous [weakening?] all round had much to do towards making our advance to have effect. Yet what must have been had we not charged is uncertain. Surely at that moment it looked very much as though the enemy would hold this ground gained and perhaps win the day.

Certain it is had Hall ‘s men first advanced, I could not possibly [have] got near the wall and the colors and men would not have been near the place where our dead were found after the battle. The fact that your father was at that wall at that time is ever be your pride. It is more valuable than any honor that could be bestowed through at the time I regarded it a mere circumstance in which I happened to be mixed up in.

Additional notes by Amos C. Plaisted:

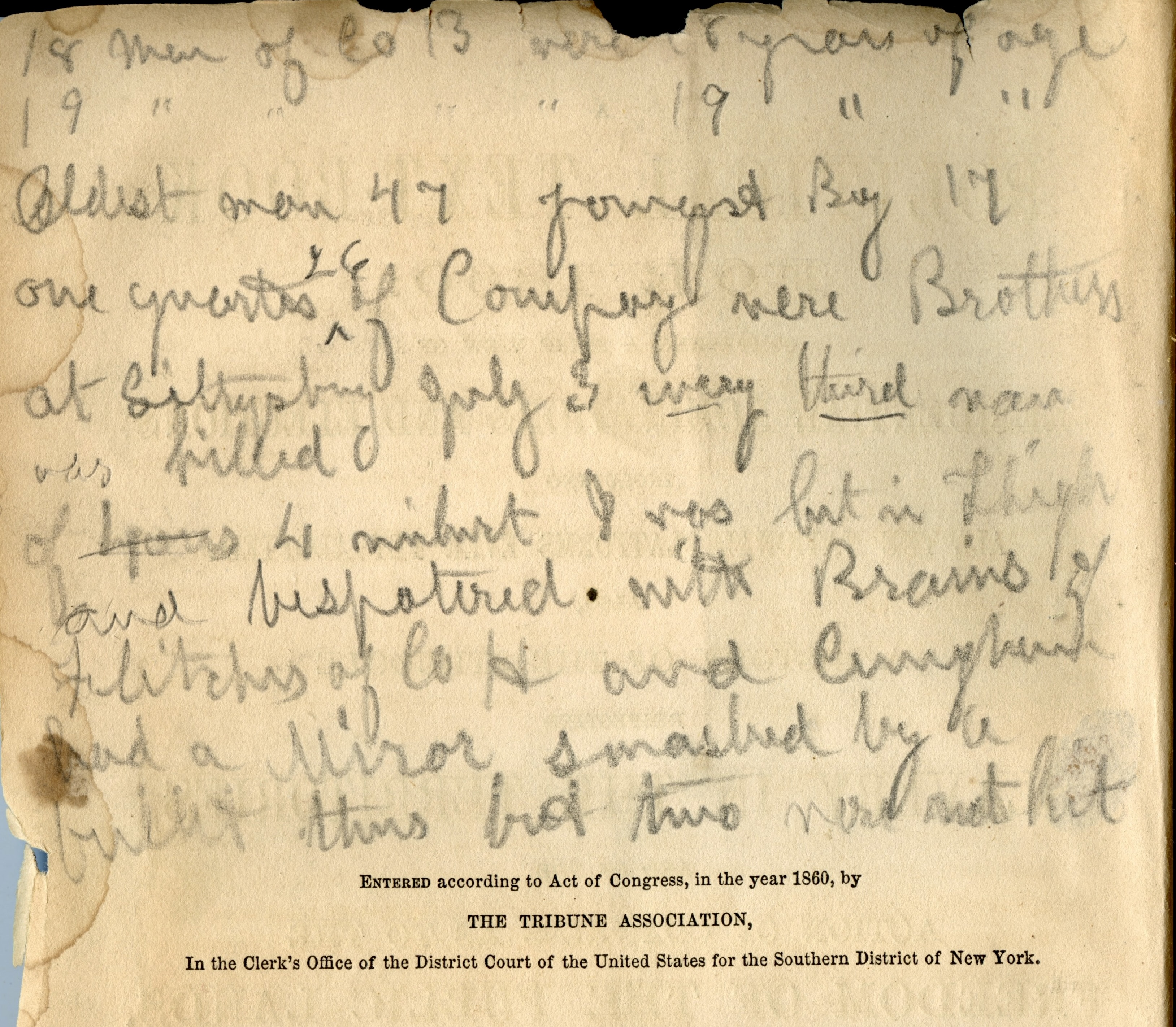

18 men of Co. B were 18 years of age

19 men of Co. B were 19 years of age.

Oldest man 47; youngest boy 17.

One quarter (26) of Co. B were brothers.

At Gettysburg, July 3rd, everything third man was killed.

Of four unhurt (at Gettysburg), I was hit in thigh and bespattered with brains of [George Fergo] Fletcher of Co. H 1 and Cunningham had a mirror smashed by a bullet; thus but two were not hit.

1 See also: “Civil War history lost…and found,” John Banks’ Civil War Blog.